December 1, 2012

December 1, 2012

By Miriam Laufer

News Writer

Book Review

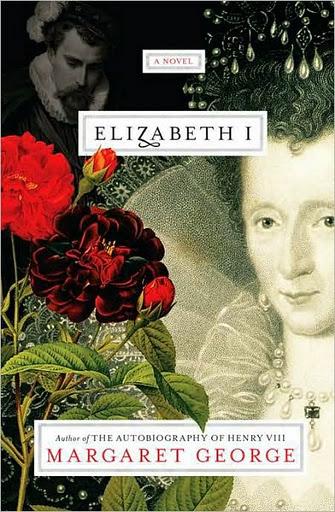

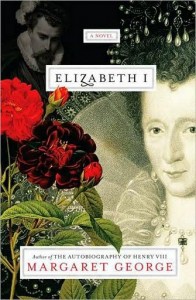

Elizabeth I

By Margaret George

Like her Autobiography of Henry VIII, Margaret George’s Elizabeth I will become a foundational text in Tudor fiction. Although authors such as Philippa Gregory, Alison Weir, and Robin Maxwell have written novels in recent memory on the Virgin Queen, in fact part of a much longer tradition of “secret histories” and plays bent on unearthing the mysteries of her private life, George surpasses them. She writes with an authority worthy of the queen herself, and brings to life arresting portraits of many Elizabethan figures, particularly the underrepresented (in Tudor fiction and biography) Laetitia Knollys and the ubiquitous William Shakespeare. Her portrayals of Robert Devereux Earl of Essex, poet Edmund Spenser, and lesser known figures like Admiral Charles Howard and his wife Catherine in particular deserve commendation.

The book is told from the points of view of Elizabeth and her estranged cousin Laetitia, or Lettice, and takes place over the last fifteen years of her reign. The two meet on only one occasion, which allows for two distinct sets of characters and settings that overlap. It opens with the imminent arrival of the 1588 Spanish Armada, the occasion of the Queen’s famous “I have the heart and stomach of a king” speech, which George executes with aplomb. Actually, numerous Armadas threaten England throughout the book, only to be vanquished by weather and bad luck. The real perpetual threat throughout the novel is the Earl of Essex, son to Lettice, and rumored lover to Elizabeth.

George makes little of the supposed love affair, except for one scene that she explains as pure invention. Instead, George shows Essex in a truly historical light; as a petulant spoiled boy filled with dreams of military glory. His own deluded beliefs about his deserts at Elizabeth’s hands and depression at her rejection of him seal his fate. George carefully builds up Essex’s interactions with Elizabeth, his long store of non-achievements, and his activities that grow ever more seditious and treasonous. He is compared to Mary, Queen of Scots in the level of threat he draws, because he is young, handsome and strong and actively courts common favor. George incorporates several of the historical popular ballads surrounding Essex, a key component of what made the historical Essex such a threat to Elizabeth’s reign. The People’s Queen could not have him playing her own game against her.

A delightful aspect of this novel is George’s obvious rapport with Shakespeare’s works and portrayal of his character. Several of Shakespeare’s plays feature in the novel; at court, in the theatre, and in dialogue between the characters. In an unlikely but charming twist, she makes Lettice Knollys Shakespeare’s Dark Lady and the Earl of Southampton the Golden Boy of the sonnets. While the latter is more likely, she does in this way sidestep the possibility of Shakespeare’s bisexuality and instead keeps his relationship to Southampton as a patron and as a fellow lover of Lettice. Even when not reciting from his plays, George’s Shakespeare uses the language one imagines he would, if he talked in a slightly more modern vernacular. It would be a boon to readers of historical fiction everywhere if George were to take on Shakespeare as her next subject.

George concentrates on important aspects of Elizabeth’s life that few of her other fictional historians spend much time on. For example, she focuses on the relationship between Elizabeth and her favorite ladies-in-waiting, especially her cousin Catherine (Carey) Howard and Marjorie Norris. Other women rarely figure in tales about Elizabeth, except as adversaries. Yet, Elizabeth was constantly surrounded by women in her private chambers. It’s amazing that few authors have found them important enough to more than mention. George also places more emphasis on Elizabeth’s adventurers, like Sir Francis Drake, Sir Walter Raleigh and even the lesser known privateers; John Hawkins, Martin Frobisher, and Sir Richard Grenville. Admittedly, these men get more attention in non-fiction, for example, in The Pirate Queen by Susan Ronald.

A recurring theme is Elizabeth’s feeling about the legacy of Henry VIII, and George’s Elizabeth does seem to regard him in an oddly positive light. Her father must have cast quite a shadow over her life, but how much she wanted to be a part of his legacy and how much she wanted to distance herself from it is another question. She kept his religion, but reversed his policies on war and spending. Fans of George’s previous work, Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, and Philippa Gregory devotees are in for a treat. This fictional biography is as great or greater in scope, understanding, and wit as Henry VIII.