April 1, 2012

April 1, 2012

Miriam Laufer

Book Critic

Book Review

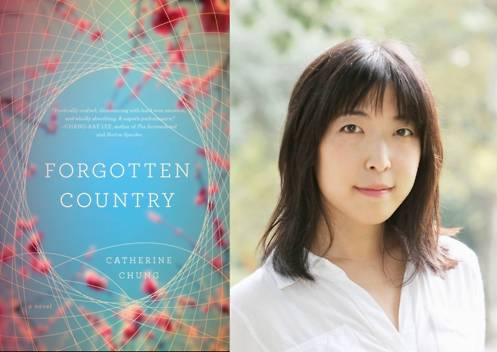

“The year that Hannah disappeared, the first frost came early, killing everything in the garden,” opens Catherine Chung’s debut novel Forgotten Country. The cyclical imagery of the garden and that mathematical precision of language are woven throughout Chung’s tale of two Korean-American sisters who, caught between the same two worlds, choose different paths for themselves. The forgotten country of the title refers both to the Korea from which their parents came — before the country was divided — and to the forgotten imaginary space of childhood where undiscovered secrets remain.

The older sister, Janie or Jeehyun, searches for her younger sister, Hannah or Haejin, at her parents’ behest. Hoping to find a clue, Janie reflects on Hannah’s behavior leading up to her disappearance. There is no sign of a struggle. Her search becomes more urgent when their father is diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer, but finding Hannah may not resolve the underlying disconnect between her and the rest of the family.

Janie’s identity is centered on being the ideal Korean daughter and sister, a role exemplified in the Korean folktales and stories from their parents’ past that she and Hannah acted out as children. The sisters took turns playing Simchung, the beautiful maiden who cast herself into the sea to save her father’s eyesight. Later, Hannah tells Janie she never liked that story, because it “teaches girls to kill themselves…it teaches them their lives are just a debt they have to pay back to someone else.” Janie explains, “The moment at which everything the father has lost was returned to him…Simchung’s life could not really begin until that moment.” The contrast between the sisters could be seen as the importance the Korean culture places on filial obedience and the American emphasis on independence collide. However, it represents our more universal struggle to shape our personal values from those of our parents and our society. Both Janie and Hannah grew up with the knowledge of their parents’ losses and the promise of their new American life, but Hannah chooses to focus on her future, while Janie tries to fulfill her father’s dreams as a mathematician through her own graduate work.

Chung’s prose rises cleanly from the page and lulls the reader with memories that build upon one another. Memories of Janie and Hannah as children allude to their parents’ childhoods — their father’s loss of nearly his entire family during the Japanese occupation and their mother’s loss of a sister to a North Korean raid. Even further back, Janie learns of her grandmother’s loss of a mother and sister, and the curse that compels her to watch closely over Hannah.

Each chapter is well organized so that, for the most part, the many time frames are clear. Though the stories are told in Janie’s voice, the memories help the reader understand the psyche of both sisters. Chung’s writing is so disciplined, however, that it runs the risk of being understated. For example, when Jeehyun and Haejin first move to the United States, their principal calls them and their mother into his office and orders them to change their names to Janie and Hannah. The change of name seems to be serious undermining of the girls’ identity and could have sparked a critique of this treatment of American immigrants (especially Asian immigrants with less “American” sounding names). Instead, the family accepts the principal’s decision and Janie barely comments on the memory in retrospect. She remarks, “It made me feel as if I belonged.” The inclusion of such an incident is clearly significant in Janie’s conception of herself, but Chung neglects to show the repercussions of this and other incidents throughout the book that should evoke a greater display of feeling.

Though Chung has garnered well-earned comparisons to prominent Asian-American authors such as Chang-Rae Lee, who also explores the boundaries between Korean and American identity, and Amy Tan, whose work epitomizes guilt-ridden relationships within families, she also deserves comparison to the likes of Pulitzer Prize winner Jhumpa Lahiri and last year’s Man Booker Prize winner Julian Barnes. Like Lahiri, Chung’s language is delicate, but taut, and the family she portrays is more reminiscent of The Namesake than The Hundred Secret Senses. Like Barnes in The Sense of an Ending, Chung is concerned with the transient nature of memory and its ability to shift in weight and permeate boundaries that are, as Janie concludes, “imaginary.”

Forgotten Country is a perceptive exercise in the geometry of the mind, an homage to the traditional culture and mythology of Korea, and a bittersweet reminder of the mingled guilt and love older sisters and brothers, sons and daughters, owe to those who raised them and those whom they helped raise.