November 1, 2012

Miriam Laufer

Book Critic

Book Review

Reading seems like an ideal pastime for a city where free access to knowledge and culture is cherished, not to mention where so many have long commutes on public transportation. During the storm that hit the area this week, books looked a lot more attractive as their electronic counterparts failed in nearly 400,000 area outages as of Monday night. In an informal survey of 22 DC metro area residents, however, only three had heard of DC Reads: One Book. One City. One Great Read., a month-long local celebration of reading.

DC Reads began October 15 and ends November 15. DC Reads Committee Chair Jameely Dahma describes the program, run by the DC Public Libraries and part of a larger international movement, as a “literacy program that promotes reading for pleasure…[using]various artistic means to discuss, display, entertain and celebrate the joy of reading.”

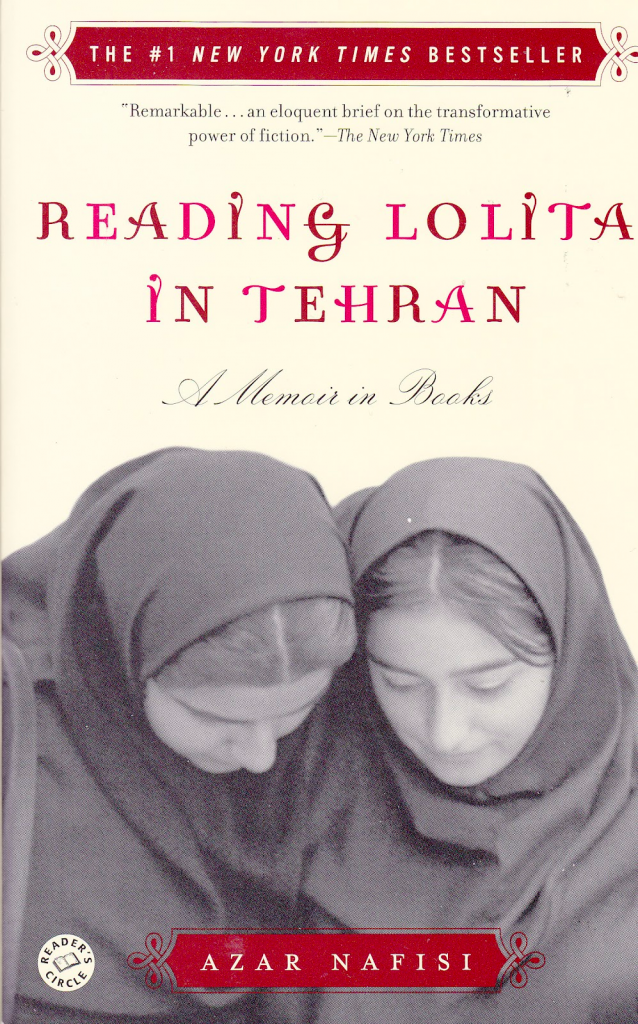

This year’s pick for Washington, D.C. is Reading Lolita in Tehran, the 2003 classic about a woman’s book club operating in secret under the oppressive Iranian regime. Azar Nafisi, the author, teaches at the Foreign Policy Institute at Johns Hopkins University in the District. According to Dahma, books for the DC Reads program are chosen by a popular vote of library staff, community partners, the Board of Library Trustees, and the Federation of Friends, considering factors such as book availability, length, film tie-ins, and connections to Washington D.C.

Reading Lolita in Tehran occupies a unique niche between fiction and non-fiction, and the DC Reads events focus on both its real and fictional contexts. The DC Public Libraries reached out to the Iranian expatriate community in the area, including organizations such as the Georgetown Iranian Cultural Society, Iranian Cultural Association of Washington, and Radio Javan. A discussion on Women in Islam will be held on November 6, along with several screenings of Iranian films Persepolis and A Separation. The book’s fictional context, specifically Nafisi’s debt to Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, is acknowledged with multiple screenings of Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film.

Whether it is dissecting cultural policy, twentieth century modernism, or both, Reading Lolita in Tehran is a rich demonstration of the power of literature to free the mind from oppression. Nafisi was a professor at the University of Allameh Tabatabai in Tehran, the capital of the Islamic Republic of Iran, until she resigned in 1995. At that time, she decided to lead an all-female book group at her home, discussing forbidden Western literature such as The Great Gatsby, Daisy Miller, and Lolita. This is a true story, but names and details of the members’ lives are changed to protect individuals, blending the reality of their lives with the fictions of the books they read.

Nafisi’s writing resembles Nabokov’s in its deft construction of an imaginary space between fiction and reality, or rather between one fiction and another. Lolita is the story of a nine-year-old girl whose life is taken over by a man who marries her mother in order to pursue his obsession with her. The book is often found controversial or distasteful, as it is told from the first person viewpoint of Humbert Humbert, the preying stepfather. Although she does not want to equate Iranian women with the helpless Lolita, Nafisi reveals the gap in Nabokov’s novel between Humbert’s imaginary Lolita and the real (fictional) Lolita. She compares it to the gap between the Islamic Republic’s imaginary modest, veiled Muslim women and the real (fictional) Muslim women in her book. She writes:

Whoever we were — and it was not really important what religion we belonged to, whether we wished to wear the veil or not, whether we observed religious norms or not –we had become the figment of someone else’s dreams. A stern ayatollah, a self-proclaimed philosopher-king had come to rule our land. He had come in the name of the past — a past that he claimed had been stolen from him. And now he wanted to re-create us in the image of that illusory past.

That freedom — to imagine ourselves, to create ourselves in the image of our own dreams — is why Americans and our literature are so frightening to the Islamic Republic of Iran and similar oppressive regimes. It’s why when Nafisi was still a professor, her students in Tehran literally put The Great Gatsby on trial. Nafisi’s book reminds us that reading and imagining can be dangerous. It suggests that oppression can be escaped, that dreams can be achieved, that even adultery, as in the case of Madame Bovary, can have its reasons.

One doesn’t need to have read any of the literature discussed in the book or even have a prior understanding of the history of the Islamic Republic in order to appreciate the women’s dilemmas and the solace they find in books. After reading, however, DC Reads has more to share. Jacki Lyden of National Public Radio will interview Nafisi on November 10 at Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library. Nafisi’s work enters another fictional realm in Elisabeth Mehl Greene’s chamber opera with performers Natalie Barrens, Carolyn Black-Sotir and Michael Langlois on November 13, also at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library.

More information and events can be found at: http://www.dclibrary.org/dcreads